The Rise of the Private Grid

America’s AI industry is building its own private power plants.

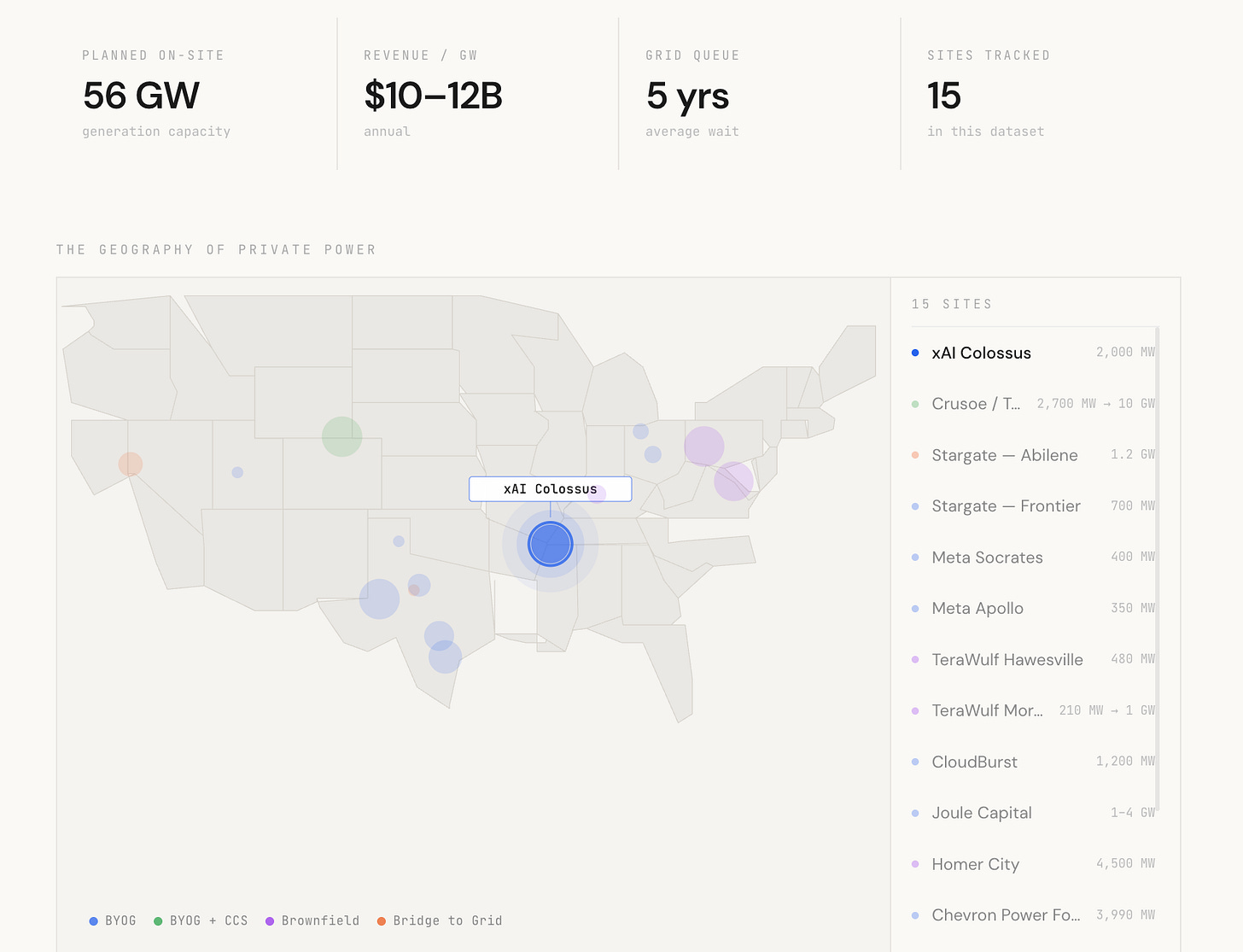

An interactive companion to this piece, with a geographic map of all major sites, technology comparisons is available here. Listen to the podcast version below.

It started in a parking lot in Memphis.

In June 2024, xAI began converting a former Electrolux factory in South Memphis into the world’s largest AI training cluster. The site had about 8 megawatts of grid power. They needed hundreds. So Elon Musk’s team did what seemed, at the time, unthinkable: they trucked in jet-engine-derived gas turbines, wired them to the building, and started generating their own electricity.

120 days later, 100,000 NVIDIA H100 GPUs were running.

That was less than two years ago. Today, what happened in Memphis has become the dominant strategy for powering AI infrastructure in the United States. It bypasses the lengthy process for connecting new loads to the grid and replaces it with something faster, cruder, and increasingly enormous: private power generation.

The Economics of Power

The economic pull is real. A single gigawatt of AI compute capacity is projected to generate $10 to $12 billion in annual cloud revenue.

But the grid interconnection queue (the formal process for connecting a new large electrical load to the public grid) now averages a wait of five years. This is how bad the backlog is: in Texas, tens of gigawatts of requests arrive monthly. Barely 1 GW gets approved in twelve months.

For the data center operator, every month of delay costs hundreds of millions in foregone revenue.

And so a new industry is born. Out of impatience. As of early 2026, 46 data centers are planning on-site power totaling 56 GW, roughly 30% of all planned U.S. datacenter capacity. A survey of 152 data center decision-makers found that a third plan to be fully off-grid by 2030, and 44% expect to rely entirely on on-site power by 2035.

They’ve decided, collectively, that they cannot afford to wait.

The Geography of Private Power

Where the new power plants are being built and why these locations were chosen

Power-advantaged locations share common traits: proximity to natural gas pipeline corridors, permissive state regulatory environments, available land, and legacy industrial infrastructure.

Texas is capturing nearly 30% of the U.S. datacenter market by 2028, driven by ERCOT’s deregulated market, fast TCEQ permitting (as quick as 22 days), and abundant pipeline capacity.

Wyoming offers sparse population, Class VI carbon sequestration well primacy, and a governor eager to replace declining coal revenue.

Ohio provides Marcellus and Utica shale gas at the wellhead.

Kentucky and Maryland brownfield sites offer something even more valuable: existing substations and transmission lines that bypass the queue entirely.

Three Paths

There are three infrastructure strategies companies are currently converging on outrun the grid. They’re not mutually exclusive, as many developers layer strategies, and the legal architecture around each one matters as much as the engineering.

Bring Your Own Generation (BYOG)

Install gas turbines or engines directly on-site. The brute force approach. Fast, capital-intensive, and increasingly systematized.

xAI pioneered it. OpenAI’s Stargate program is scaling it to 10 GW across the U.S. Meta is deploying four different types of turbines and engines at a single Ohio site because no single manufacturer can deliver enough units on time.

Most BYOG projects are “behind the meter”, meaning the generators sit on the data center’s side of the utility connection. The legal foundation is straightforward: under the Federal Power Act, generating electricity on your own property for your own use doesn’t trigger utility regulation. You’re not selling power. You’re consuming it.

This has inspired some creative workarounds. Companies like Solaris and VoltaGrid operate an “energy-as-a-service” model, so they own the turbines and sell power directly to the data center. To avoid being classified as utilities, they’ve built structures designed to blur the line: equipment leases, managed service agreements, and joint ventures. For instance, xAI’s Stateline Power LLC is structured as 50.1% Solaris, 49.9% xAI… just enough to maintain the designation of self-generation.

The extreme version of this strategy is fully islanded: no grid connection, no utility meter, no interconnection agreement, no transmission charges, no FERC jurisdiction. Legally invisible. Stargate’s Project Frontier in Shackelford County, Texas with 210 Jenbacher engines, 700 MW, entirely off-grid, is the purest expression of this model. Joule Capital’s Utah site runs the same playbook.

Senator Cotton’s DATA Act of 2026 would make this explicit, exempting fully off-grid facilities from federal power regulation entirely.

The Brownfield Play

Buy former industrial facilities that already have heavy power infrastructure.

This is the TeraWulf play. They acquired a former Century Aluminum smelter in Hawesville, Kentucky for $200 million, which came with 250 acres already fitted with 480 MW of existing power, energized substations, and high-voltage transmission lines.

The company also picked up a former 210 MW coal plant in Morgantown, Maryland near Northern Virginia. These are sites that took decades and billions to build. They’re being repurposed in months.

The legal advantage here is different from BYOG. Brownfield sites typically land front-of-the-meter; fully grid-connected, subject to utility tariffs and capacity markets. But the existing connection is the point: the infrastructure is already permitted, already built, already energized.

Bridge to Grid

Use on-site generation as primary power until a permanent grid connection is secured, then transition the turbines to backup.

This is how most developers frame the strategy publicly. Stargate’s Abilene campus runs on-site gas with 29 GE turbines providing nearly a gigawatt of generation while the grid connection scales up.

It’s politically palatable. It’s probably true in some cases. But once turbines are paid off and natural gas stays cheap, the economics of continuing to run them are compelling. Bridges have a way of becoming permanent.

The Machines Behind The Power

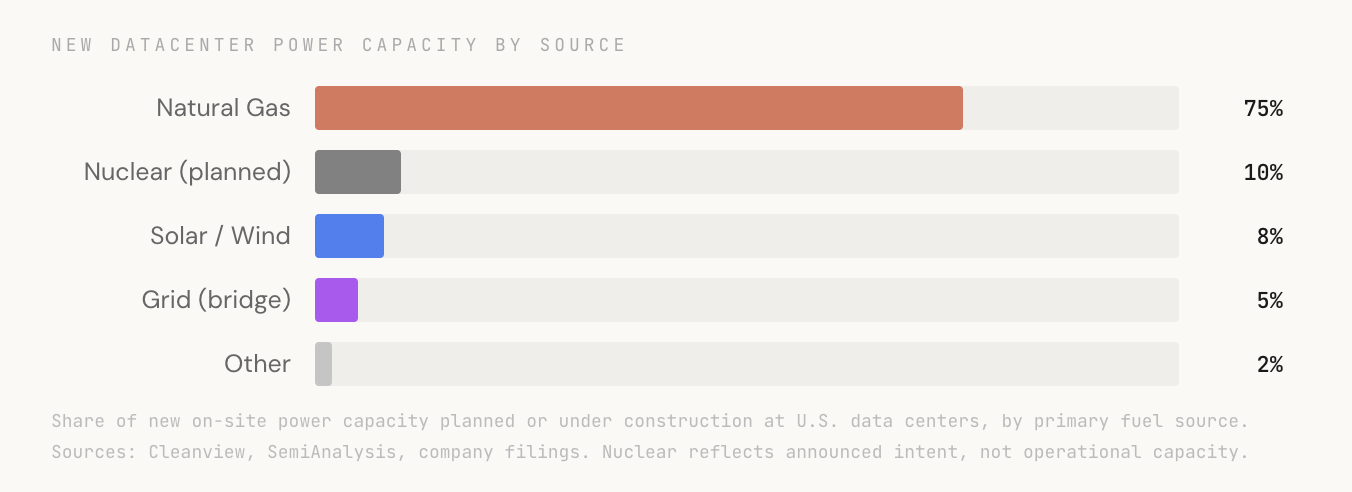

Nearly 75% of new power capacity being built for data centers runs on natural gas. The reason is simple: it’s abundant, it’s dispatchable, and critically, it can be deployed now.

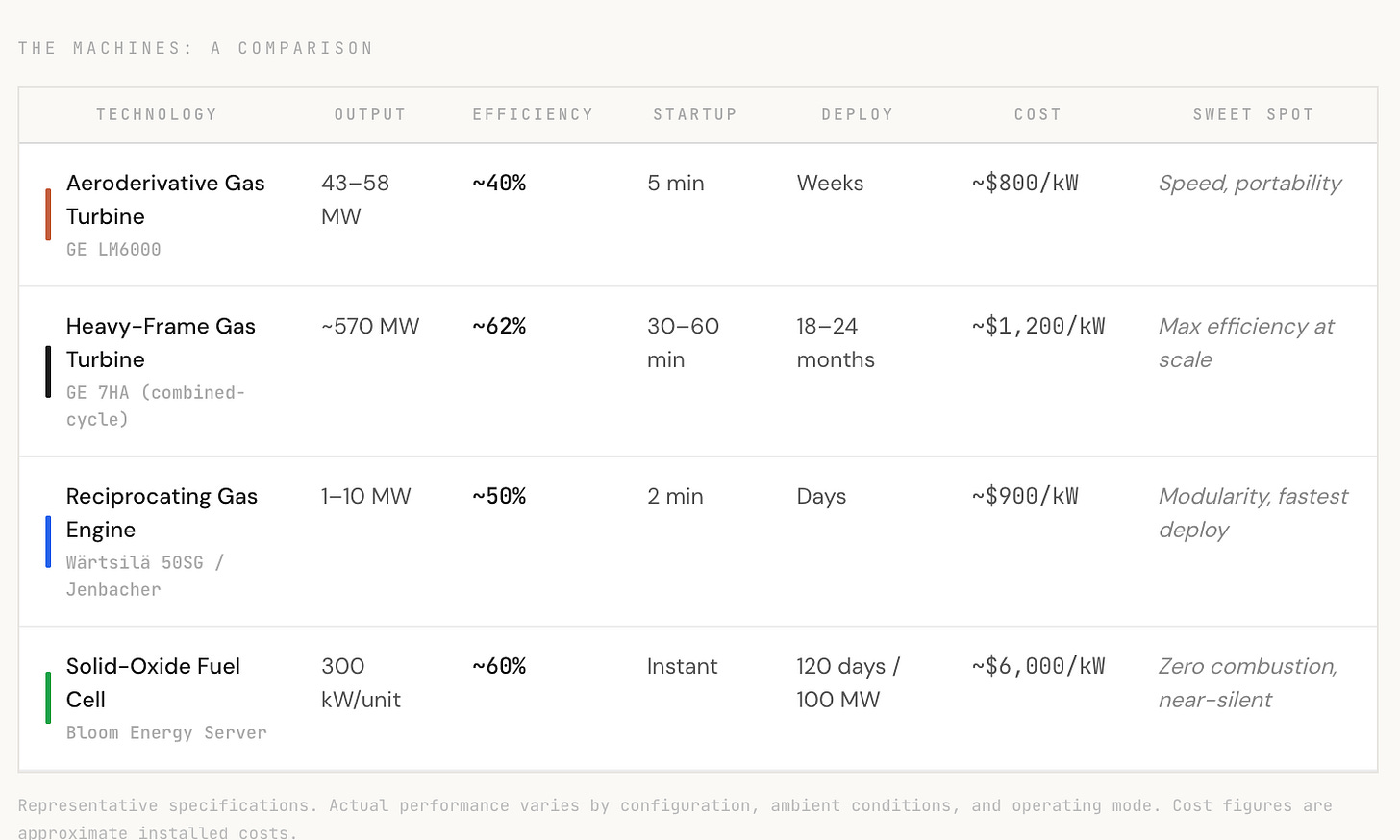

The equipment falls into four categories:

Aeroderivative gas turbines, basically modified jet engines, are the workhorse. GE Vernova’s LM6000 produces 43–58 MW, starts in five minutes, and ships 95% factory-assembled. They are sold out through 2028 to 2029, with backlogs approaching 80 GW.

Heavy-frame gas turbines are bigger, slower to deploy, and far more efficient. In combined-cycle configuration, where waste heat drives a secondary steam turbine, they hit ~62% efficiency, the highest of any combustion technology. This is the oil majors’ bet: Chevron’s Power Foundries are built around seven GE Vernova 7HA units, each producing roughly 570 MW. ExxonMobil and NextEra are planning similar combined-cycle plants with integrated carbon capture.

Reciprocating gas engines offer ~50% efficiency and maximum modularity. Wärtsilä’s 50SG reaches full load in two minutes. VoltaGrid’s truck-mounted Jenbacher generators (the ones xAI used first) can arrive on-site and produce power within days. This is the fastest-growing segment.

Solid-oxide fuel cells convert gas to electricity electrochemically. This means no combustion, no NOx, no water, almost no noise. Bloom Energy’s units run at ~60% efficiency and can deploy 100 MW in 120 days. The trade-off is cost: roughly $6,000/kW. But the company has signed deals worth billions with AEP, Brookfield, Oracle, and others, and is doubling manufacturing capacity to 2 GW/year. Its stock is up ~450% in the past year.

Nuclear remains the stated long-term ambition for several projects. For instance, Fermi America has filed NRC applications for four Westinghouse AP1000 reactors at its Texas Panhandle site.. but no reactor is delivering power to a data center today.

But for now, gas is the answer to the question.

The Parallel Power Network Emerging

What began as individual acts of infrastructure desperation is becoming something more structural. A parallel power system.

Williams Companies has committed $5.1 billion to datacenter power generation and reports being “overwhelmed” with developer inquiries. Kinder Morgan has $9.3 billion in pipeline projects, half for power demand. Energy Transfer signed the first-ever direct gas-to-datacenter supply deal.

We’re watching a parallel industrial supply chain building itself in real time.

We’ve been here before

In the 1880s, in the early days of American electrification, any business that wanted electricity had to generate its own. Edison created a separate company just for selling self-contained dynamo systems to factories, hotels, and mills. J.P. Morgan had a personal generator installed in his Madison Avenue basement.

By 1887, Edison’s “isolated plants” far outnumbered his central stations. There were only 103 central stations in operation nationwide, while hundreds of private plants hummed inside individual buildings.

Each factory was an electrical island. Each one needed its own boiler, its own engine, its own engineer. The systems were expensive, redundant, and ran at a fraction of their capacity most of the day. Two-thirds of early electric companies didn’t even offer daytime service. Demand for lighting peaked in the morning and evening, and generators sat idle in between.

It took Samuel Insull to see the inefficiency. Edison’s former private secretary, who had moved to Chicago to run a struggling local utility, realized that the problem was fragmentation. If you consolidated many small loads into one large station, you could run the generators more hours of the day, spread fixed costs across more customers, and drive the price of electricity down far enough to reach not just factories and mansions but ordinary homes.

He called it “massing production” of electricity itself.

By 1907, Insull had merged Chicago’s five competing electric companies into Commonwealth Edison. He pioneered tiered pricing (charging different rates for peak and off-peak usage) and pushed for ever-larger steam turbines that could serve entire districts from a single station.

By 1930, his utilities served 5,000 communities across 32 states, generating a tenth of the nation’s electricity. This became the architecture of American electrification. It brought electricity to homes, farms, and small businesses that could never have afforded their own isolated plant.

A century later, the largest electricity consumers in the country are rebuilding the system Insull replaced. Private generation, behind-the-meter interconnection, islanded microgrids. The engineering is more sophisticated, but the structure is familiar: the wealthiest users building their own supply and stepping outside the shared system.

The obvious case against private power generation is that it fragments a shared system. Fixed costs like transmission maintenance, grid reliability, capacity planning are now spread across fewer ratepayers.

But the obvious case for it is just as strong: if the largest electricity consumers build their own supply, they stop driving up costs for everyone else.

In Virginia, the infrastructure Dominion Energy is building to serve data center demand, like new gas plants, transmission lines, substations, is projected to add $14 to $37 per month to a typical household bill by 2040 in order to cover these new infrastructure costs. If those data centers had generated their own power from the start, much of that buildout wouldn’t be needed.

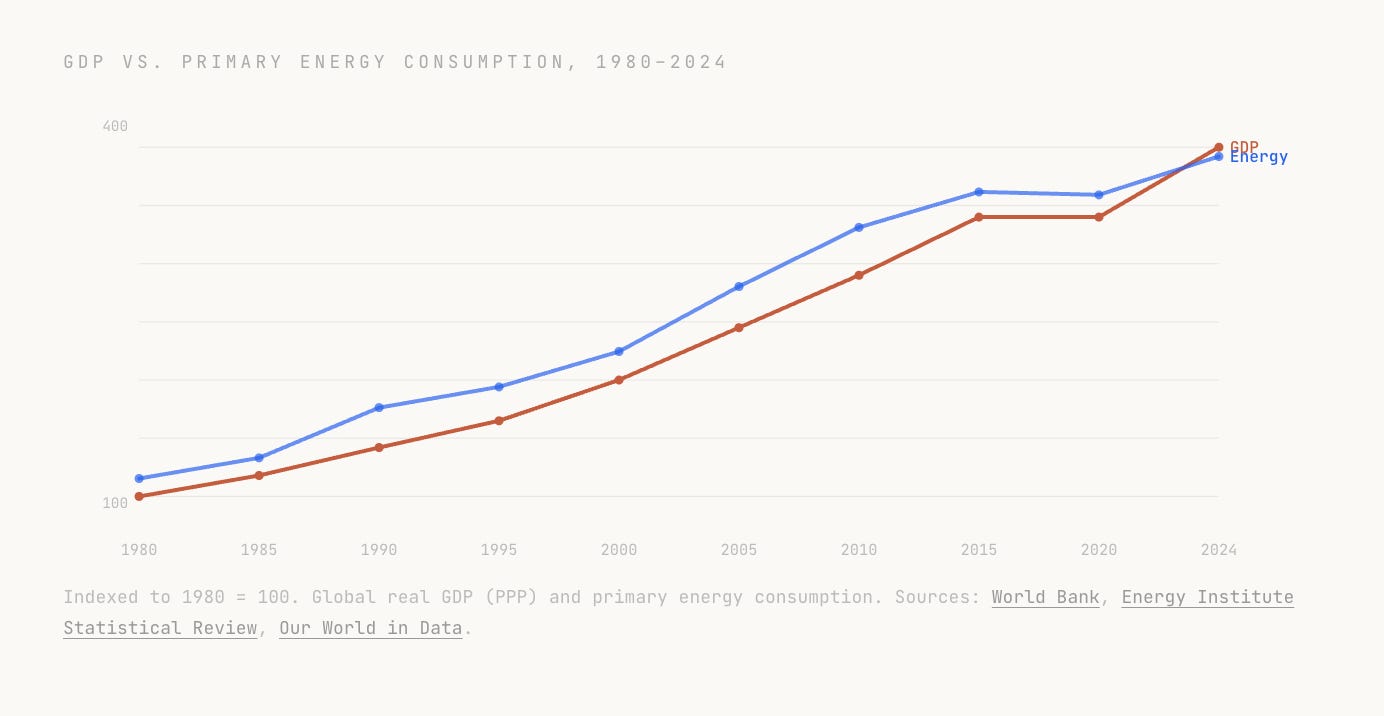

Prosperity is energy-intensive

Josh T. Smith, who writes the energy policy newsletter Powering Spaceship Earth, frames the case for all of this simply: prosperity is energy-intensive.

There is no pathway to broad-based prosperity that involves using less power.

Josh T.Smith

This sentiment captures the philosophical core of the private power movement: energy demand isn’t an externality to minimize. It’s a feature of progress.

The optimists are probably right that AI requires enormous amounts of energy, and that building it is a net positive.

The question is whether the way we’re building it —by bifurcating private and shared infrastructure— creates a permanent divide between those who can afford their own grid and those who can’t.

Sources: SemiAnalysis, Cleanview, Grid Strategies, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, FERC filings, TCEQ permits, company press releases and SEC filings. Data current as of February 2026.