The Rise of AI Co-Scientists

Novel breakthroughs or Integration layers? Early evidence suggests this is where value accrues first.

With the tools we have today, we could have discovered the transformer architecture four years earlier than we did.

At least that’s what simulations from early co-scientist systems suggest, according to scientists I spoke with at NeurIPS and at an AI4Science event hosted by FutureHouse.

The claim is difficult to validate. But the reasoning behind it is straightforward. The key ideas behind the transformer (attention mechanisms, sequence-to-sequence models, positional encoding) existed across separate research communities for years before Vaswani and the Google team combined them in 2017 in the seminal Attention is All You Need paper.

If even directionally correct, this points to a thesis that’s increasingly hard to ignore: the first major milestone in AI for science may not be a breakthrough model or a novel reasoning architecture. It may be the integration layer (workflow orchestration, retrieval, synthesis) that helps researchers find non-obvious connections across the existing body of knowledge.

We may already have a proof point. When Demis Hassabis and John Jumper won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for AlphaFold2, the achievement was often framed as an AI breakthrough.

But structurally, AlphaFold2 was largely an integration achievement: it combined attention mechanisms from NLP, evolutionary covariance data from genomics, and decades of experimental protein structures into a single coherent system.

It introduced novel architectural ideas, particularly around geometric reasoning, but the core ingredients existed. The breakthrough was in seeing how they fit together.

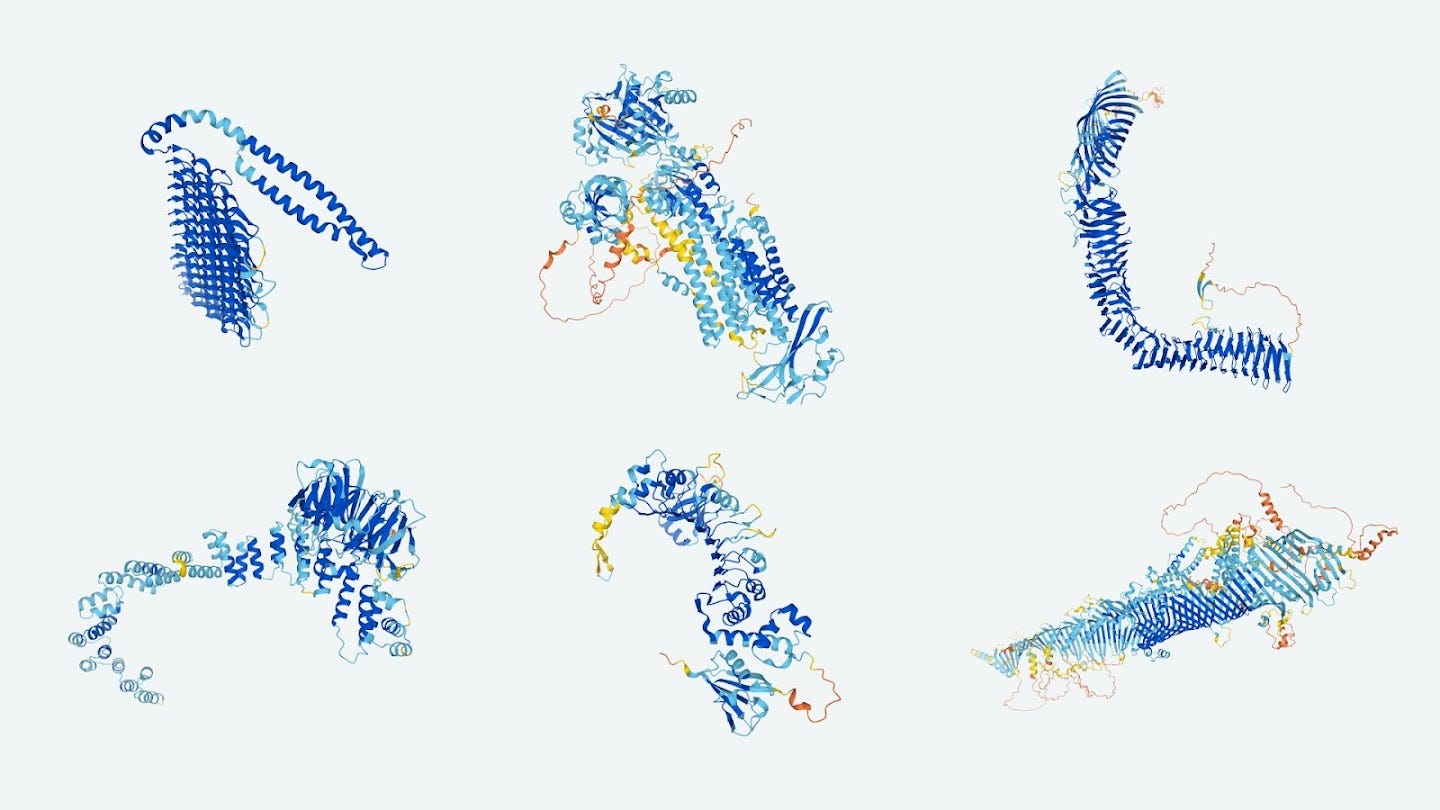

Deepmind later open sourced the AlphaFold Protein Structure database, a massive database of over 200 million protein structure predictions to accelerate scientific research.

In the past few years, over $3 billion has rapidly poured into startups working on AI-powered tools for scientific discovery. From Sakana AI’s $379M to build systems that write academic papers for $15 each, to Periodic Labs and Lila Sciences’ $300M+ raises to build scientific superintelligence, to Xaira and Isomorphic Labs’ combined $1.6B to apply AI to therapeutics, the list goes on.

Much of this investment targets improved domain-specific models, reasoning capabilities, or automated lab infrastructure, which make them bold, moonshot bets.

There is an argument that the integration layer may matter more in the short term, at least until we hit problems that require genuine theoretical leaps rather than recombination of existing knowledge.

Just in the past year or so, many of the top AI research labs and a number of startups have released early versions of their AI “co-scientists”; from OpenAI’s Prism, Google’s Co-Scientist, and Anthropic’s move into the life sciences, to early companies like Phylo, Intology, and Edison Scientific. These tools aim to give researchers a coherent environment to conduct and automate work across the full arc of research, from hypothesis generation to experimentation to paper writing.

Early evidence suggests this is where value accrues first.

FutureHouse‘s trajectory is instructive: their first validated therapeutic candidate (ripasudil for dry macular degeneration) came not from ether0, their chemistry reasoning model, but from Robin, a workflow that chains together literature retrieval, synthesis, and data analysis agents. The system connected glaucoma research to macular degeneration research, surfacing a ROCK inhibitor already approved for one eye condition as a candidate for another.

Similarly, while companies like Unreasonable Labs are building novel reasoning architectures beyond standard LLMs, they appear equally focused on the work environment that scientists will engage with first.

This sequencing makes sense: the integration layer is what surfaces the right data and coordinates workflows, giving reasoning models something meaningful to act on.

As one AI4Science researcher puts it: “Science, in many ways, is really a process of reinventing the wheel over and over again in different fields, and bringing learnings from one field into another.”

This brings us to the caveat worth stating explicitly. The integration layer thesis holds strongest for problems that are fundamentally recombinatory, i.e. where the key ideas already exist but sit in separate literatures, separate disciplines, separate mental models.

But science also produces problems that require genuine theoretical leaps. The kind where no amount of retrieval across existing literature would surface the answer because the answer hasn’t been articulated yet. General relativity didn’t emerge from better cross-referencing of Newtonian mechanics papers. For those problems, the reasoning layer (or something beyond current architectures entirely) will need to lead.

The honest assessment is that most of day-to-day science is recombinatory. I would argue that the gains from AI in science may not be primarily about efficiency, like saving researchers time on literature reviews or administrative work.

They may be about direction: reshaping which questions get asked, which connections get surfaced, which fields talk to each other. If the integration layer can accelerate that cross-pollination, it may matter more in the near term than breakthroughs in reasoning architectures or solutions to data scarcity.

Mason Rodriguez Rand is a Strange Research Fellow who holds degrees in molecular and mechanical engineering (UChicago, UC Berkeley) and has led engineering and go-to-market efforts at climate and energy startups out of Argonne National Lab and UC Berkeley, spanning nuclear, carbon removal, and advanced materials.