ASML's 30-Year Monopoly: The Moonshot Bet No One Can Replicate

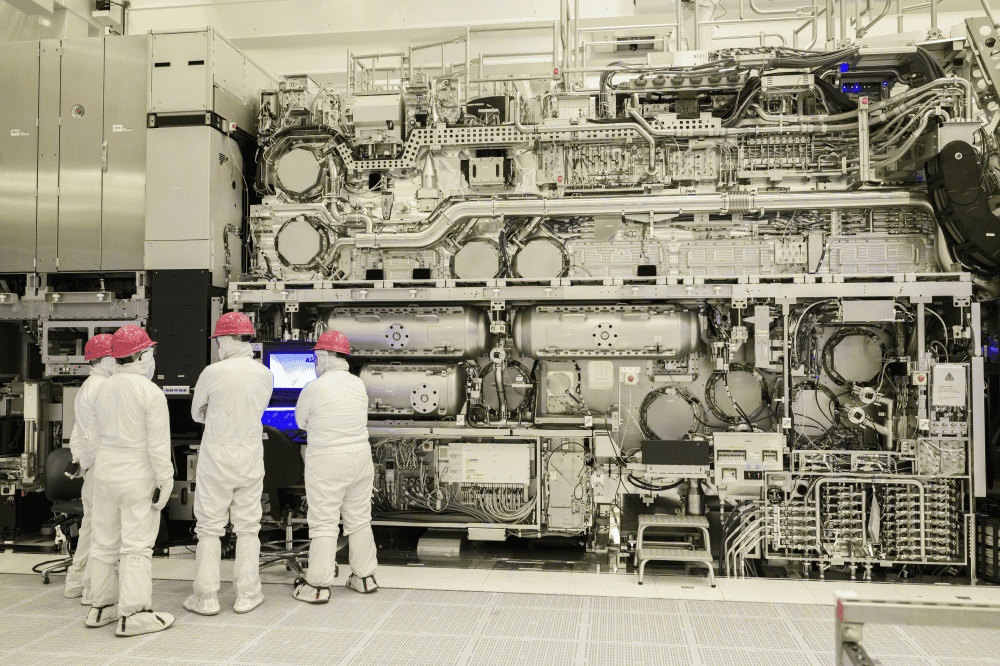

One of the most extraordinary returns on R&D might be a machine that costs $380 million, weighs 180 tons, and took three decades to perfect.

Only one company on Earth can make the machines that make the future possible.

In a nondescript facility in Veldhoven, Netherlands, ASML produces what might be the ultimate competitive moat: extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) machines.

EUV machines makes cutting-edge semiconductors possible. And ASML has a 100% monopoly on this market. No other company in the world can build them. It’s not hyperbole to call this one of the greatest R&D payoffs in history.

The Insanity of What They Do

To understand why ASML’s achievement is so remarkable, we need to grasp what extreme ultraviolet lithography actually does.

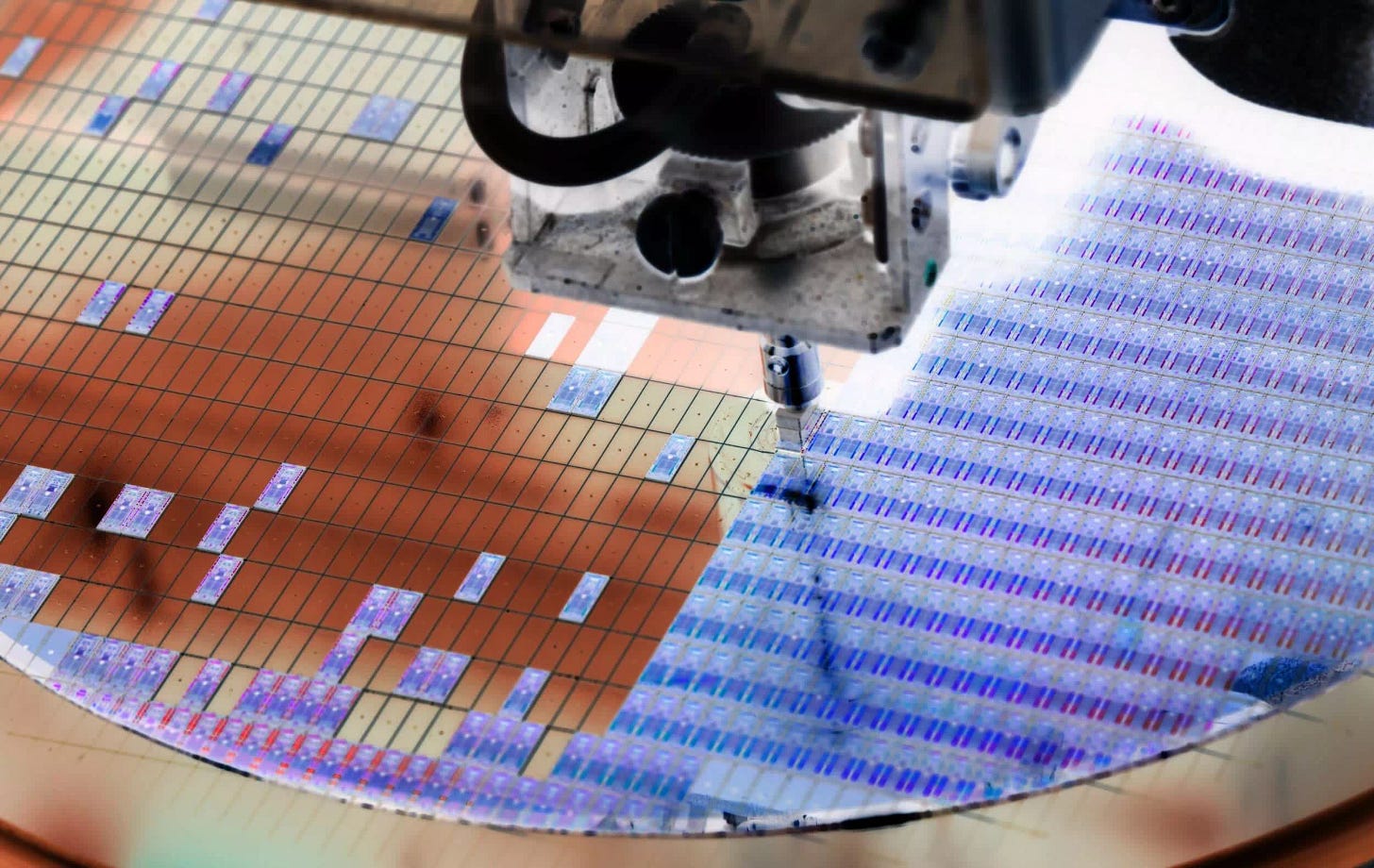

Modern computer chips are built by etching microscopically thin patterns onto silicon wafers. The smaller the pattern, the more transistors you can pack onto a chip, and the more powerful your processor becomes. But there’s a fundamental physics problem: you can only etch patterns as small as the wavelength of light you’re using.

ASML’s EUV machines use light with a wavelength of just 13.5 nanometers (this is roughly 1/5000th the width of a human hair… like sketching blueprints on a grain of rice.). To generate this light, they drop microscopic tin droplets into a vacuum chamber, then blast each droplet twice with a laser 50,000 times per second. The resulting plasma emits the EUV light needed to etch patterns just a few atoms wide.

The engineering challenges are absurd. EUV light is absorbed by everything so the entire process has to happen in a vacuum. The mirrors must be perfectly smooth to within a single atom. The whole system requires components from over 800 suppliers across the globe, including the world’s most advanced optics from Germany’s Zeiss, which took 15 years to develop.

ASML didn’t stumble into this monopoly. The company’s origins trace back to the 1980s, when it spun out of Dutch electronics giant Philips. While American and Japanese competitors focused on incremental improvements to existing lithography technology, ASML - after years of building conventional deep ultraviolet (DUV) technology - made an audacious, moonshot bet: EUV would be the future.

The development process was punishing. ASML began serious EUV research in the 1990s as part of an international consortium. That R&D journey would stretch over two decades, with early prototypes plagued by catastrophic reliability problems, like prone to constant breakdowns, unable to maintain production speeds. These were problems no one had solved before because no one had ever tried to industrialize extreme ultraviolet light.

ASML continued to pour billions into R&D, often spending 15-20% of annual revenue on research. The company nearly went bankrupt multiple times. Competitors dropped out. Customers like Intel, Samsung, and TSMC eventually had to invest directly in ASML to keep the EUV program alive.

Roughly 30 years after serious research began, the first production EUV machines were finally ready.

When they arrived, they redefined what was possible. Today, every cutting-edge chip in your smartphone, your laptop, the data centers running AI, requires ASML’s machines. There is no alternative. The company shipped around 380 lithography systems in 2024 (including 40+ EUV machines), generating over €28 billion in total revenue.

Why can’t anyone else build these machines?

Technical complexity. The decades of accumulated knowledge, the 800-supplier ecosystem, the atom-level precision required. But the deeper answer is time.

Even if a competitor had unlimited funding and could poach ASML’s entire engineering team, they’d face an insurmountable problem: 30 years of iterative improvements, dead-ends discovered and avoided, supplier relationships forged through shared problem-solving, and manufacturing processes refined through trial and error. You can’t compress that learning curve. China has reportedly invested tens of billions trying to develop domestic EUV capability. They’re at least a decade behind, possibly further.

ASML’s monopoly has become a chokepoint in the global technology supply chain. In 2024, the U.S. government pressured the Netherlands to restrict ASML’s sales to China, kneecapping China’s ability to manufacture advanced chips

What’s the Next ASML?

This raises a central question for understanding deep tech moats (what we care about at Strange Ventures): where is the next R&D investment that will create an equivalent moat?

We look for these characteristics:

Fundamental physics problems that require genuine innovation, not just engineering scale

Development processes and timelines that create natural barriers to competition

Essential status for an entire industry or technological paradigm

These are the technologies where you can’t just copy what someone else did. The learning is in the doing, accumulated through years of frustration and failures.

Does hype ruin everything?

The key question to ask is: would ASML have survived long enough to invent EUV in today’s environment?

ASML succeeded partly because it pursued long-term R&D in a highly collaborative way. Early backing from its corporate partner Philips gave it room to experiment. Later, billion-dollar investment partnerships with customers who needed the technology as much as ASML did.

That deep alignment allowed ASML to stay independent, weather near-bankruptcies, and keep investing long after most firms would have been acquired, shut down, or forced to chase faster returns.

Does that environment still exist? Modern capital markets are less patient. Disruptive technologies get acquired before they mature. Geopolitical tensions fracture global collaboration. Today’s mega-investments (AI frontier labs, fusion startups, quantum computing, etc) operate under entirely different conditions.

ASML’s monopoly was built in a different era of globalization. One where 800 suppliers across multiple countries could collaborate on a single machine, where a Dutch company could sell to Chinese customers without political interference.

The irony is that ASML’s success might have killed the conditions that made it possible.

The machines in Veldhoven might be monuments to a specific moment… when patient capital, international cooperation, and dogged, multi-decade vision could still create something truly unreplicable.

The question is whether we’ll see their like again.

If you’re an inventor working on true breakthrough technology, you can always find us at Strange Ventures.